Source: PBS

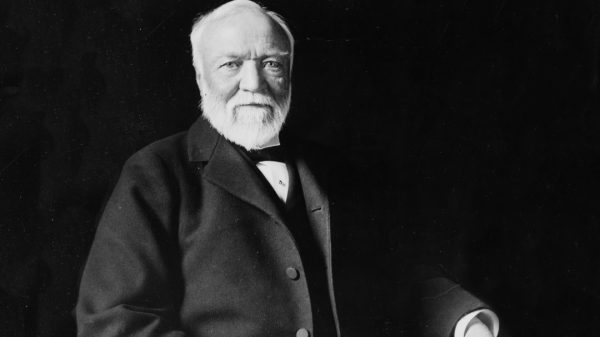

The father of the transatlantic cable, Cyrus Field was a savvy paper merchant who knew nothing about telegraphy but readily understood the commercial possibilities of connecting Europe and America. Driven to succeed yet patient in times of failure, Field kept the cable project going for twelve long years, crossing the Atlantic more than 30 times in an effort to raise money, solve problems, and make his cable a reality. His ultimate success ushered in a new era of international communications.

Good Business Sense

Cyrus Field was one of ten children of the Reverend David Dudley Field, four of whom, like their father, would ultimately find a place in the Dictionary of American Biography. Apprenticed at age 16 to New York City dry goods store owner A. T. Stewart, Cyrus did well enough that his salary was doubled each year until he left to join the paper wholesaler E. Root and Company. When that company foundered, Field acquired its stock and settled E. Root’s debts even though he was not legally required to do so, a move that cemented his growing reputation. Soon wealthy enough to build a large house in Gramercy Park, Field grew bored with the paper business. When his brother Matthew introduced him in January 1854 to telegraph company owner Frederick Gisborne, Field was all ears. After hearing Gisborne’s proposal to build a telegraph connecting Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, Field took the idea one step further and proposed a cable from Ireland to Newfoundland that would shorten the time for communications from Europe to America by about two weeks.

Confident Salesman

Never one to waste time (when traveling abroad, the first word he learned in each new language was “faster”), Field quickly got the wealthy New York associates of his Cable Cabinet to pledge $1.5 million for the project. The first phase of their enterprise, running a telegraph through the Newfoundland wilderness and then across the Cabot Strait to Nova Scotia, took more than a year longer than expected, and Field set off for England in the summer of 1856 to raise more money. There he arranged to meet the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Clarendon, whom Field impressed with his confident American manner. “Suppose you make the attempt and fail — your cable is lost at sea — then what will you do?” Lord Clarendon wondered. “Charge it to profit and loss,” Field replied, “and go to work to lay another.” Field’s manner helped win him significant assistance from the British government, and in early 1857 he was able to secure matching terms from the United States.

The First Attempts

By the summer of 1857, the first cable had been constructed and loaded on the U.S.S. Niagara and the H.M.S. Agamemnon. On August 5, Field spoke at a magnificent send-off on the shores of Valentia Bay, Ireland. “I have no words,” he said, “to express the feelings which fill my heart tonight — it beats with love and affection for every man, woman, and child who hears me.” In a sort of benediction for the transatlantic cable, Field turned to the Bible: “What God has joined together, let no man put asunder.”

Determination

The next twelve months tested Field’s confidence. The 1857 attempt failed when the cable snapped about 200 miles from shore. When Field replaced the lost cable and tried again in June 1858, a ferocious storm nearly sank the Agamemnon, and then her cable snapped after she had traveled only about 100 miles from the mid-Atlantic starting point.

When a third expedition began in July 1858, Field was beginning to feel the strain. “When I thought of all that we had passed through, of the hopes thus far disappointed, of the friends saddened by our reverses…. I felt a load at my heart almost too heavy to bear.” He wasn’t ready to give up, though: “My confidence was firm and my determination fixed.”

Courage, Energy and Perseverance

The next few years were difficult. The Civil War delayed the cable project, and Field still needed more money. A committee of inquiry laid some of the blame for failure at Field’s feet; his haste had resulted in a faulty cable, badly prepared to reach all the way across the Atlantic. But Field would not abandon his dream. By July of 1865, he was able to mount another expedition. This time he had a better cable and the Great Eastern, a ship capable of carrying the entire load.

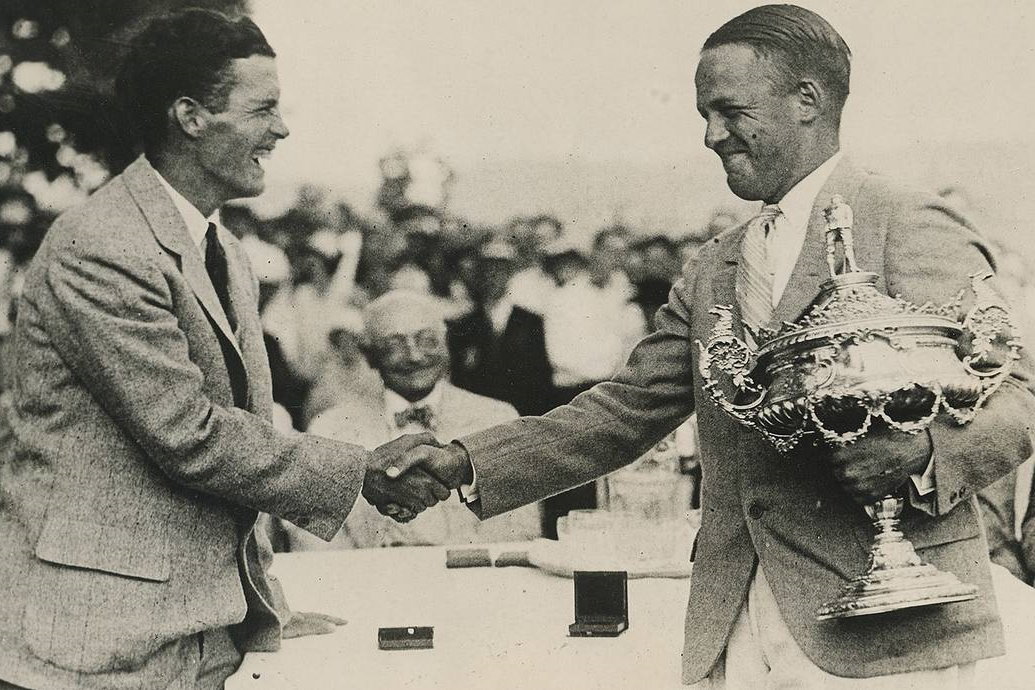

When a freak accident ended the expedition just 600 miles from Newfoundland, Field remained upbeat. “We’ve learned a great deal,” he said, “and next summer we’ll lay the cable without a doubt.” In this Field was man of his word. In July 1866 the second transatlantic cable was successfully laid and this time it would not give out. Field was hailed as a hero, and among other honors, given a gold medal by Congress. When he died at the age of 72, having lost his fortune to Wall Street, the simple epitaph on his tombstone nicely summarized his monumental achievement: “Cyrus West Field, To whose courage, energy and perseverance, the world owes the Atlantic telegraph.”